10 Consonance

Consonance is a fundamental principle in Western music that describes how ‘harmonious’ a collection of notes sound when played together. It is particularly important in polyphonic music composition, where many different musical parts play at the same time. In particular, it is used to determine which kinds of musical sonorities are treated as stable and which are treated as unstable, something which helps drive the temporal dynamics of lots of Western tonal music.

When we study consonance from a psychological perspective, we typically distil it down to a very basic question: what makes some chords sound consonant, and others sound dissonant? Is it just a cultural convention, or does it come down to deeper acoustic or psychological processes?

In order to study consonance in psychological experiments, we need to have an operational definition of consonance. In this psychological context, we typically consider consonance to be a perceptual quality of a chord: something subjective in the mind of the listener, like pitch or loudness. The question is then, how do we access that perceptual quality?

One approach is simply to ask the participant, “how consonant is this chord”? However, consonance is arguably specialist musical terminology, and it does not always translate well across languages.

In practice, psychologists therefore often use an alternative question, “how pleasant is this chord?”. The assumption here is that consonance is essentially equivalent to subjective pleasantness, at least when a chord is presented in isolation. This approach seems to work well, and has successfully been applied cross-culturally. However, it should be noted that some researchers dispute this operationalisation, and say that the word ‘consonance’ cannot be replaced in this context. Whether this makes any meaningful difference in practice is still a matter for debate…

Having operationalised consonance as perceived pleasantness, we can then do experiments to quantify how consonant particular chords are perceived to be in practice. In a given trial of the experiment, we might for example play the participant a particular musical chord, and ask them to rate the pleasantness of this chord on a multiple choice scale. Now, we can’t read all that much into an individual trial, because subjective judgments like pleasantness are typically variable on an individual basis, and often differ between participants. So, in practice we would play the same sound to many participants, get ratings from each of them, and then average these ratings to get an overall ‘consonance rating for the chord’. We can repeat this process for many different chords, systematically characterising the perceived pleasantness for each one.

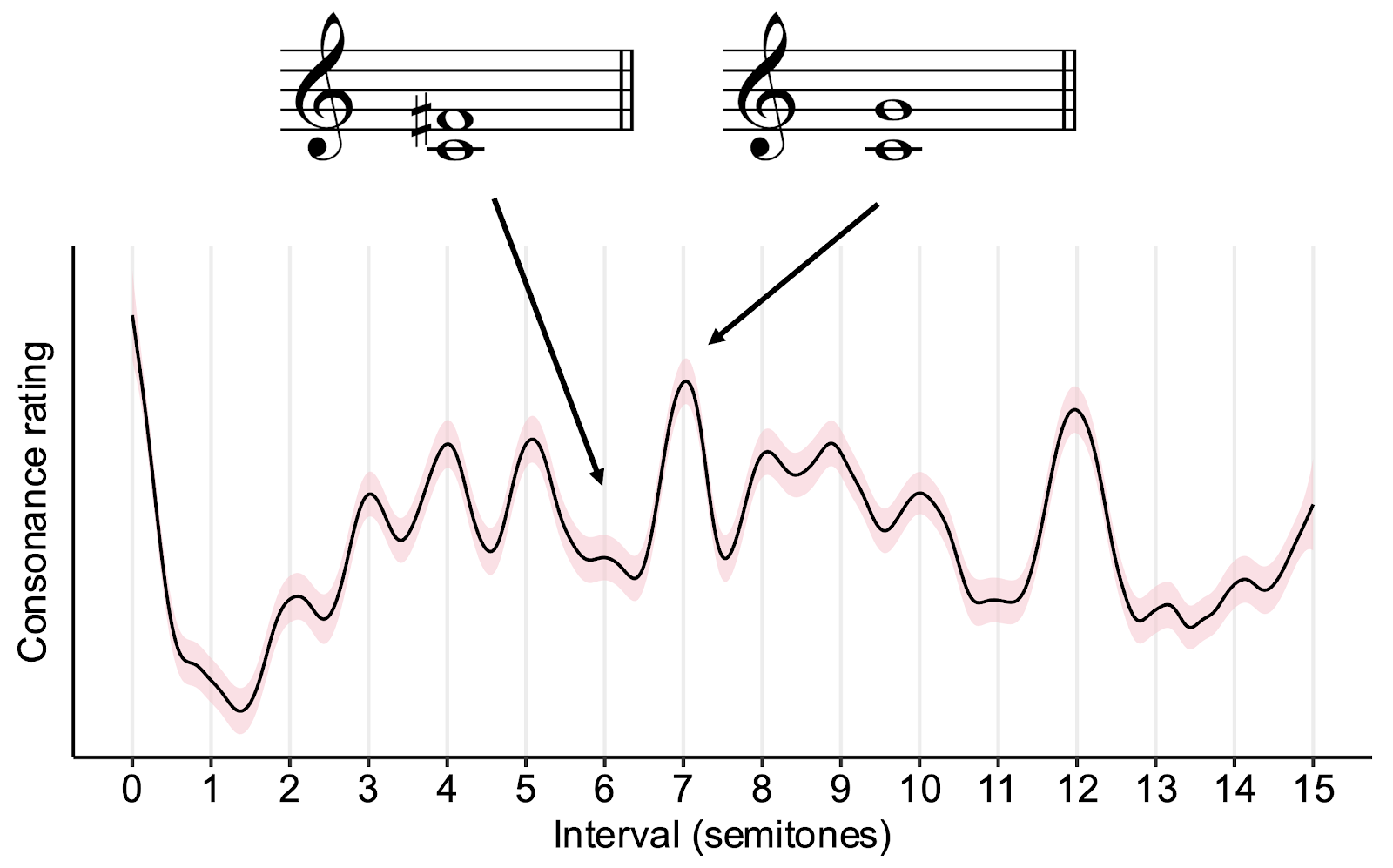

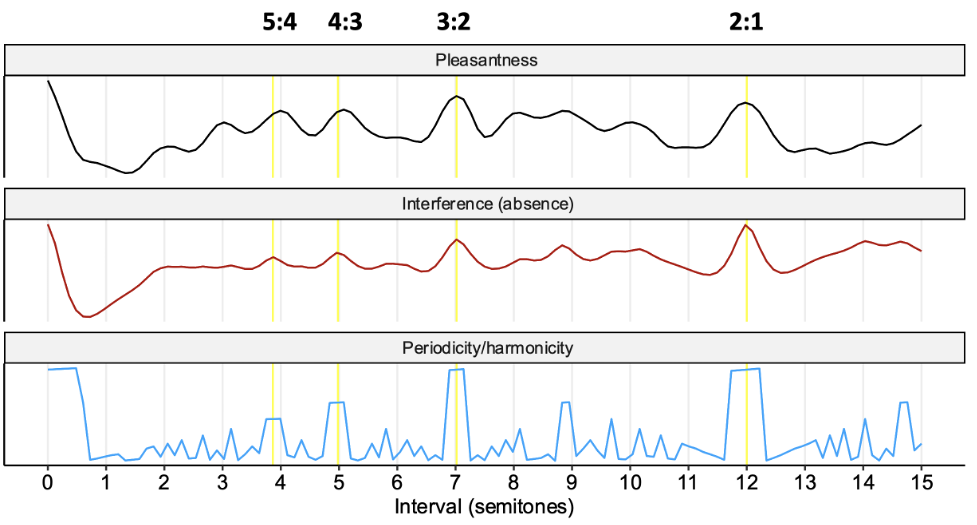

If we do this for all dyads between 0 and 15 semitones, we get a graph like the following:

Data from Marjieh, Harrison, Lee, Deligiannaki, & Jacoby. (in preparation), collected from behavioural experiments with US participants. Shaded regions correspond to +/- 1 standard error, computed over trials after normalising within participants.

Here we have intervals in semitones plotted on the horizontal axis, and aggregated consonance ratings plotted on the vertical axis. We see lots of peaks at integer values of semitones, showing us that dyads are most consonant (to Westerners) when they correspond to intervals from the Western 12-tone scale. Within this 12-tone scale, we still see lots of variation, though. For example, we see a big peak at 7 semitones, corresponding to the perfect fifth, in contrast to a minimal peak at 6 semitones (the tritone). Our challenge is then to explain these peaks and valleys, both in the context of simple dyads and in the context of more complex three- and four-note chords.

10.1 Theories of consonance

Many different theories of consonance have been presented over the centuries, and some have proved to be more effective than others. Here we are going to focus on three theories that have survived the most criticism, and that seem to provide the best candidates for explaining the data that we get from consonance experiments:

Periodicity/harmonicity

Interference between partials

Cultural familiarity

10.1.1 Periodicity and harmonicity

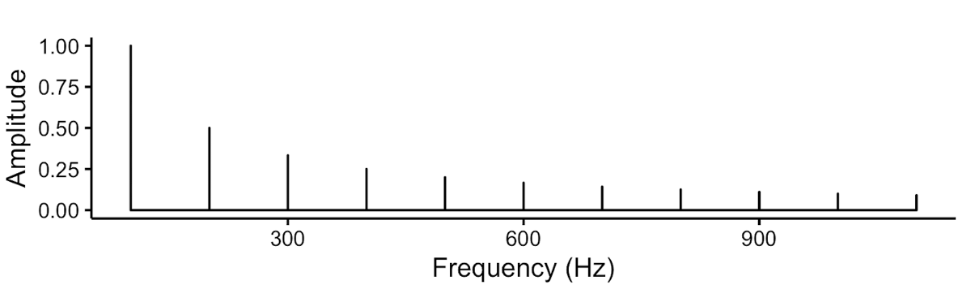

In Chapter 7 we introduced the notion of a harmonic complex tone, an idealised kind of tone built only out of frequency components that are integer multiples of a common fundamental frequency. When a sound has this property of frequency components largely corresponding to integer multiples of a common fundamental frequency, we say that the spectrum has high harmonicity.

Idealised harmonic spectrum with a fundamental frequency of 100 Hz.

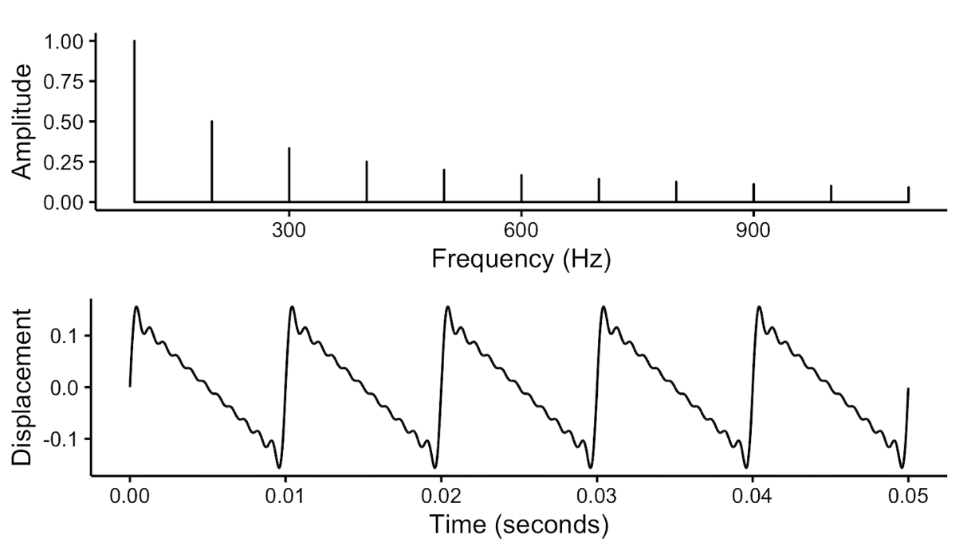

Harmonicity is something that we observe by looking at the sound’s frequency-domain representation. If we then look at the waveform in its temporal representation, we see the consequence of this harmonicity: a highly periodic waveform, that repeats itself at a set time period. It turns out that periodicity and harmonicity are deeply linked from a mathematical perspective, and typically go hand-in-hand.

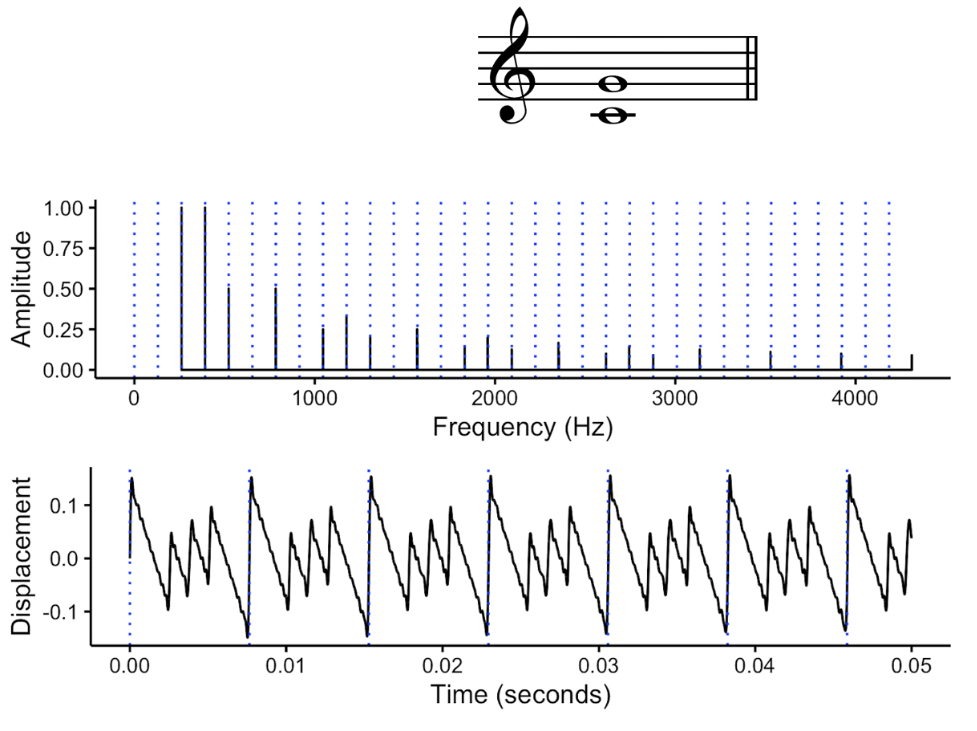

A harmonic complex tone with a fundamental frequency of 100 Hz expressed in both the spectral (top) and temporal (bottom) domains.

Certain musical chords share these properties of harmonicity and periodicity. Take the perfect fifth, for example. The perfect fifth is built from approximately a 3:2 frequency ratio, and hence several of the harmonics in each tone overlap with one another. Moreover, it turns out that the partials in the resulting spectrum all end up being multiples of a common fundamental frequency, corresponding to one octave below the lowest tone. So, we can say that the perfect fifth exhibits high harmonicity. The claim is then that the high harmonicity and periodicity of the perfect fifth is what makes it pleasant, or consonant.

The harmonicity and periodicity of the perfect fifth.

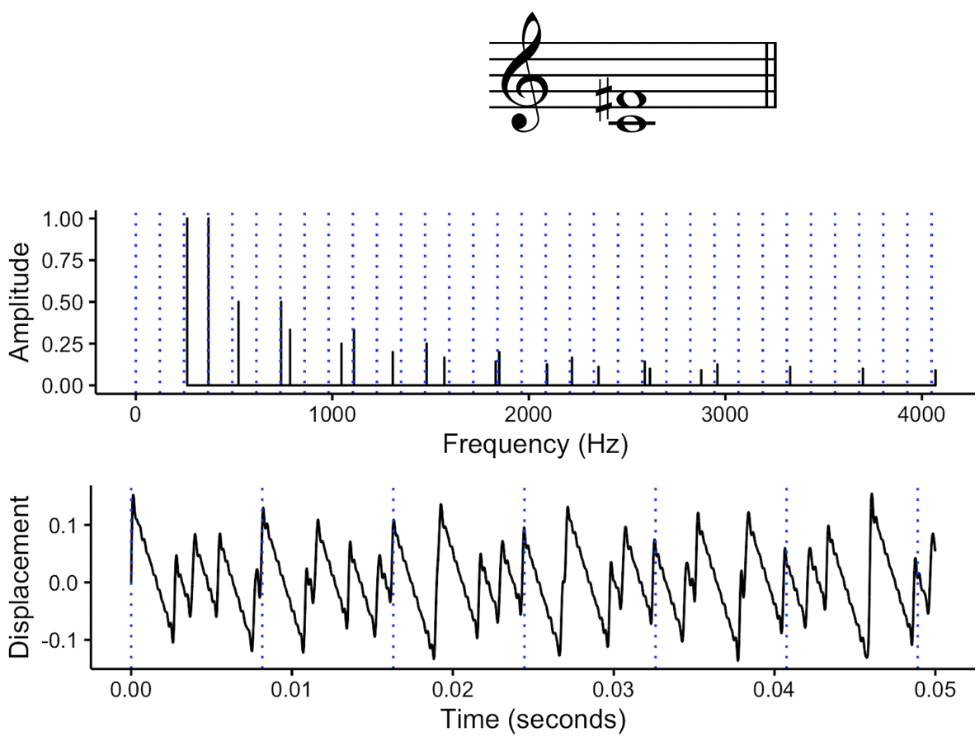

In contrast, the tritone behaves in an opposite way to the perfect fifth. Its spectrum does not relate clearly to any harmonic template, and its waveform is not periodic in any clear way.

The low harmonicity and limited periodicity of the tritone.

There are various suggestions as to why humans might consider harmonicity and periodicity to be pleasant. One is that humans like harmonicity because harmonic sounds correspond to a simpler, easier to process auditory environment. Another suggestion is that humans like harmonicity because harmonicity is associated with vocalisations, and vocalisations are important features of the environment to pay attention to. A third suggestion is that humans don’t have any innate preferences for harmonicity, but learn such preferences through cultural exposure.

10.1.2 Interference between partials

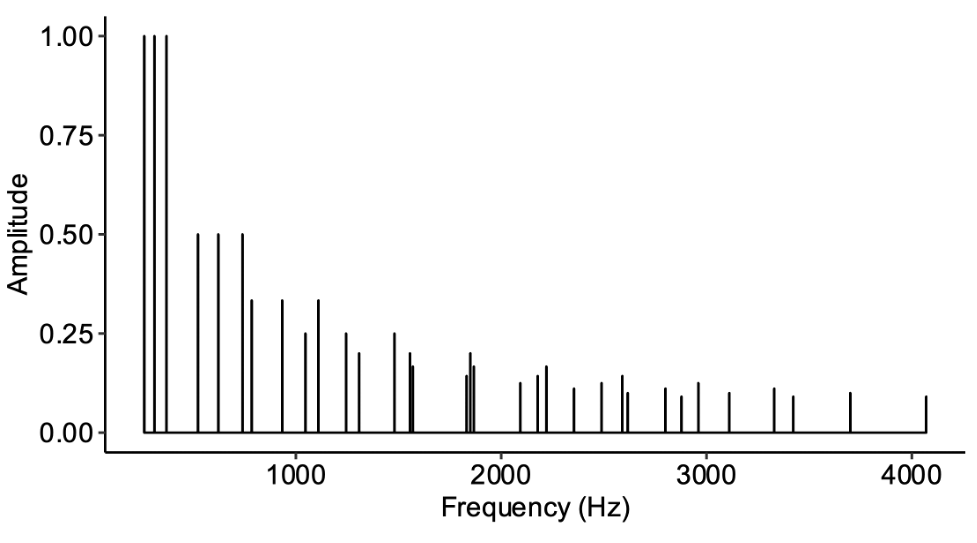

We already know that musical chords can be expressed in a spectral form, where we plot the frequency and amplitude of every notional pure tone component in the chord. A spectrum for a diminished triad might look like this.

Interference theories of consonance claim that consonance comes from the absence of unpleasant interactions between neighbouring partials in this spectrum. The nature of these interactions has been studied in psychoacoustic experiments where researchers play participants pairs of pure tones separated by a variable distance, and ask them to rate the pleasantness of the combination. It turns out that the combination sounds quite pleasant when the two tones are almost overlapping, or when they are far apart, but when they are a small distance apart (approximately a semitone apart) they elicit an unpleasant interference effect. There are two main suggestions for why pairs of partials interact negatively in this way: beating and masking. Let’s discuss both in turn.

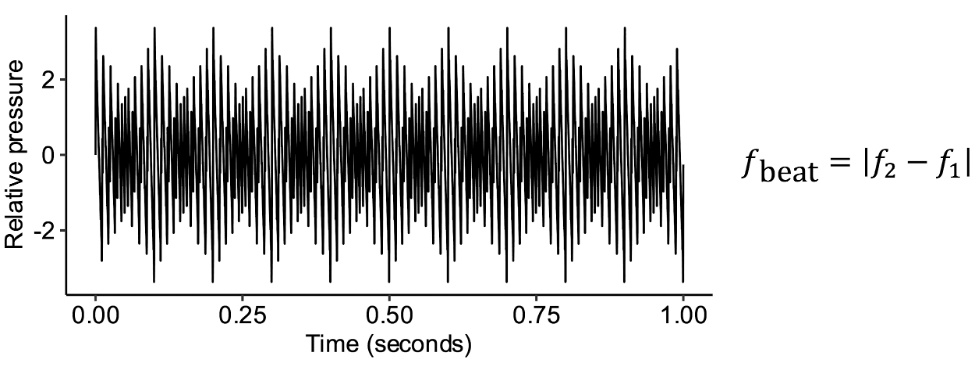

Beating. When you add two sine waves together, both of similar frequencies, it turns out that the resulting waveform ends up oscillating in amplitude in what is called a ‘beating’ effect. The frequency of this amplitude oscillation corresponds to the difference in frequency between the two sine waves. At certain frequencies, typically between about 20 and 30 Hz, this beating tends to feel unpleasant, causing a perceptual sensation that we term ‘roughness’.

Beating resulting from combining pure tones of 400 Hz and 430 Hz.

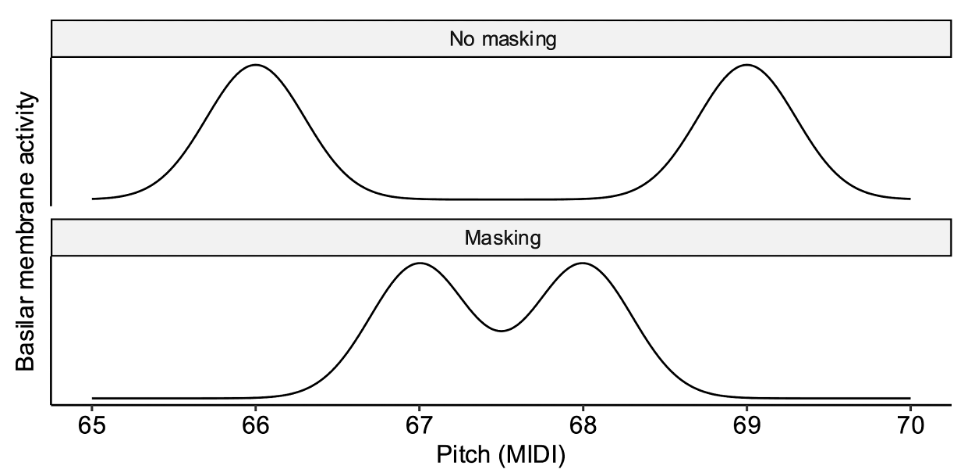

Masking. Masking concerns the auditory system’s ability to resolve, or ‘hear out’, different partials in the acoustic spectrum. When partials are well-separated, they are easy to distinguish, because they stimulate distinct parts of the basilar membrane. However, when partials are close together, they end up stimulating overlapping regions, which makes them hard to distinguish, and causes what is known as ‘masking’. It is thought that this masking effect might feel unpleasant, because it reflects an auditory environment that is hard to process accurately.

Schematic illustration, not to scale

It is thought that both beating and masking depend closely on the notion of auditory filters, discussed in Chapter 9 in the context of pitch perception. As a reminder, each location on the basilar membrane can be modelled as a kind of auditory filter centred on that location’s characteristic frequency, with this filter selectively retaining frequency components in the neighbourhood of that characteristic frequency. In particular, two partials are thought to interfere with each other only if they are both resolved within the same auditory filter. When partials are localised to different auditory filters, they do not end up being superposed, and hence do not produce beating effects. Furthermore, if the partials are localised to different auditory filters, this makes it easy for the brain to distinguish them from one another, hence reducing masking.

According to interference theories of consonance, these unpleasant pairwise interactions (stemming potentially from beating and masking) accumulate across all the different pairs of partials within a chord. The consonance of a chord therefore depends on the extent to which it manages to avoid these kinds of negative interactions.

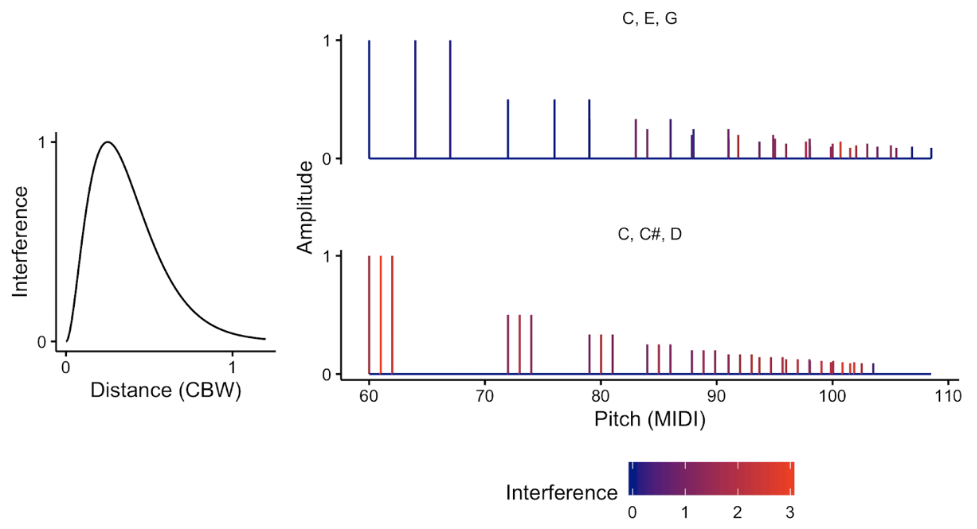

Here are two illustrative spectra for visualising the contribution of interference to consonance and dissonance. The first corresponds to a C major triad; the nature of its pitch intervals means that many of its tones’ harmonics overlap neatly with each other, or else give each other a wide berth. As a result, the partials only experience a minimal amount of interference, which here is marked in red. In contrast, the second spectrum corresponds to a three-semitone cluster chord, C C# D. Here the harmonics do not overlap neatly with each other, but instead sit in prime locations for eliciting interference. The interference theories therefore correctly predict that this chord will be perceived as unpleasant, or dissonant.

It’s worth pointing out now that periodicity, harmonicity, and interference theories all predict that intervals based on simple integer frequency ratios should be consonant. Simple frequency ratios produce harmonic chords by definition, because their fundamental frequencies are all integer multiples of a common frequency. This has the mathematical consequence of the chords being also periodic. It turns out that this integer-ratio property tends also to minimise interference, because it means that the harmonics in the chord tones tend to overlap neatly with each other.

| Interval | Frequency ratio | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Unison | 1:1 | Consonant |

| Major second | 9:8 | Dissonant |

| Major third | 5:4 | Consonant |

| Perfect fourth | 4:3 | Consonant |

| Perfect fifth | 3:2 | Consonant |

| Major sixth | 5:3 | Consonant |

| Major seventh | 15:8 | Dissonant |

| Octave | 2:1 | Consonant |

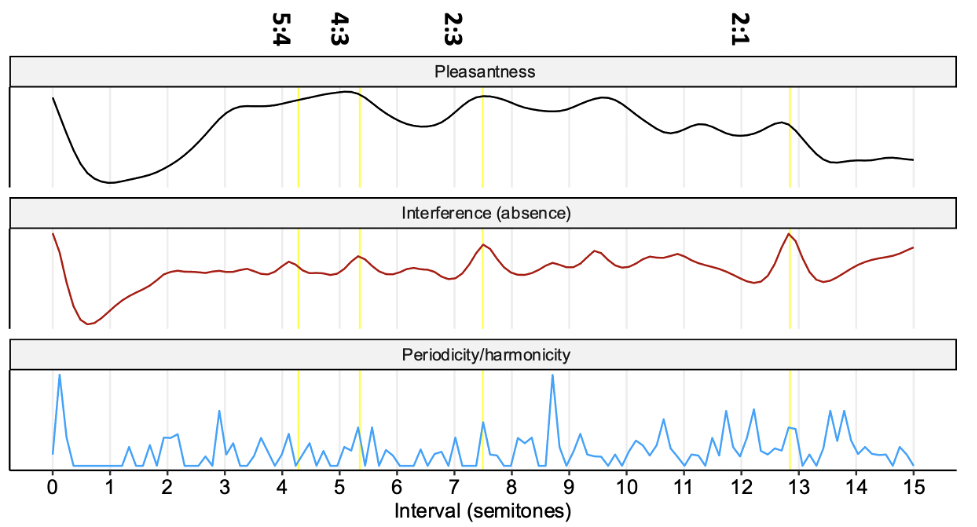

We can visualise this common property of the theories by operationalising each theory as a computational model, and plotting its predictions for different dyadic intervals. Here I’ve plotted the Hutchinson-Knopoff interference model in red (Hutchinson & Knopoff, 1978) and a periodicity model in blue (derived from the Praat sound analysis toolbox), for comparison against empirical pleasantness ratings from participants. In addition, I’ve placed yellow lines corresponding to the simplest integer frequency ratios: 5:4, which is the major third, 4:3, which is the perfect fourth, 3:2, which is the perfect fifth, and 2:1, which is the octave. We can see that both models successfully predict the consonance of these intervals. See Section 27.3.3 for a more in-depth exposition of the Hutchinson-Knopoff algorithm.

Data from Marjieh, Harrison, Lee, Deligiannaki, & Jacoby. (in preparation)

10.1.3 Cultural familiarity

The cultural familiarity theory is perhaps the simplest of the three. It states that humans do not have any innate predisposition to perceive certain chords as consonant and others as dissonant. Rather, it claims that these preferences are learnt through exposure: in particular, chords that the individual experiences many times in their lifetime begin to be experienced as pleasant, in what is known as the ‘mere exposure effect’. This mere exposure effect is a well-established phenomenon in many psychological domains.

In the context of Western listeners, we can model the cultural familiarity of chords through corpus analyses of popular music, studying how often different chord types appear. This figure illustrates the results of such an analysis, conducted on the McGill Billboard Corpus of popular music. As we might expect, the four most prevalent chords in this corpus correspond to major and minor chords in triad and seventh form. Each of these chords is generally perceived as very consonant by Western listeners, consistent with the theory.

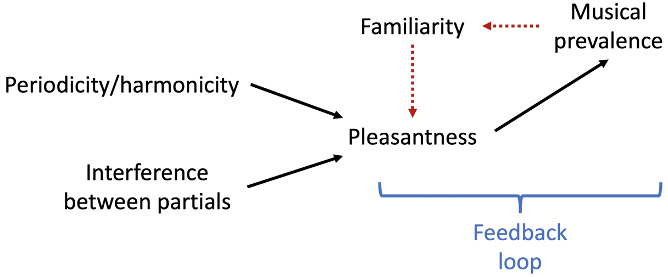

However, we have a chicken and egg problem here, concerning the different possible causal directions between pleasantness and familiarity. On the one hand, on the level of an individual listener, it is quite plausible that musical prevalence comes first (since lots of music was composed before the listeners’ birth), and that this musical prevalence engenders familiarity, and therefore pleasantness. On the other hand, the prevalence of simple integer frequency ratios in the music has to come from somewhere – it would be a strange coincidence for this phenomenon to arise without there being some kind of human predisposition to be sensitive to these ratios, as mediated through periodicity, harmonicity, or interference between partials.

One possibility is that cultural learning provides a feedback loop that amplifies the perceptual effects of periodicity, harmonicity, and interference on pleasantness. Perhaps initially the effects of these features are slight, and not salient to most listeners. However, this slight effect has a slight effect on music composition, causing listeners to become more familiar with integer-based frequency ratios, and hence to perceive these frequency ratios as more pleasant than before. This effect then feeds back into music composition, and so on and so on, producing a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

10.2 Disentangling consonance theories

Disentangling these different theories is hard because, on the face of it, all the theories make similar predictions. Chords that exhibit low interference tend also to exhibit high periodicity and high cultural familiarity. This makes it hard to design experiments that can support one theory while discrediting another.

Four different approaches have proved particularly useful for tackling this entanglement problem in recent years:

Studying different cultural groups;

Studying individual differences in consonance perception;

Studying consonance perception using different tone spectra;

Regression modelling.

Let’s consider each in turn.

10.2.1 Cultural groups

In the last few years a research group from MIT has performed a series of studies with the Tsimane’ people, an indigenous group from Bolivia with very little exposure to Western culture (J. H. McDermott et al., 2016). It turns out that participants from this group exhibit no preferences for Western consonance: for example, they do not prefer major triads to diminished triads. This is consistent with the idea that culture plays an important role in shaping consonance perception.

Moreover, one can find several musical cultures across the world that seem to actively promote the kinds of pitch intervals that Westerners would consider to be dissonant. It doesn’t seem like these musicians are insensitive to the particular aesthetic effect of these intervals, like it seemed for the Tsimane’ people; instead, it seems like the particular acoustic effects of these intervals are being intrinsically valued in these musical styles. There are not many formal psychological studies of people from these cultures, but music recordings from these cultures are very suggestive. Here’s one such recording of a group of Bosnian Ganga singers:

A performance by a group of Bosnian Ganga singers. Credit: Pantelis N. Vassilakis, http://acousticslab.org/RECA220/

10.2.2 Individual differences in consonance perception

The second strategy is the individual differences approach. This approach relies on the observation that preferences for certain auditory features tend to vary between participants. For example, some people have particularly strong preferences for consonant chords, whereas others are quite happy to hear dissonant chords. Likewise, people might differ in the extent to which they prefer harmonicity, or the extent to which they dislike interference between partials.

There is one main study in the literature that pursues this approach (McDermott et al., 2010). After a series of experiments with Western listeners, they concluded that consonance preferences correlated with preferences for harmonicity, but not with aversion to interference5. On the face of it, this provides strong support for harmonicity theories of consonance perception, and against interference theories. However, there is still a little scepticism in the field about the generalisability of the results. Operationalising preference in a clean way is always difficult, and it’s important to be sure that the experimental methods are really measuring consonance, harmonicity, and interference preferences in the way that is claimed.

10.2.3 Tone spectra

A third strategy is to explore consonance with different tone spectra. The idea is that, if we replace the harmonic spectrum with some other cleverly chosen tone spectrum, then the different theories such as harmonicity and interference theories will start making different predictions from each other, helping us to explain what’s really underlying consonance perception.

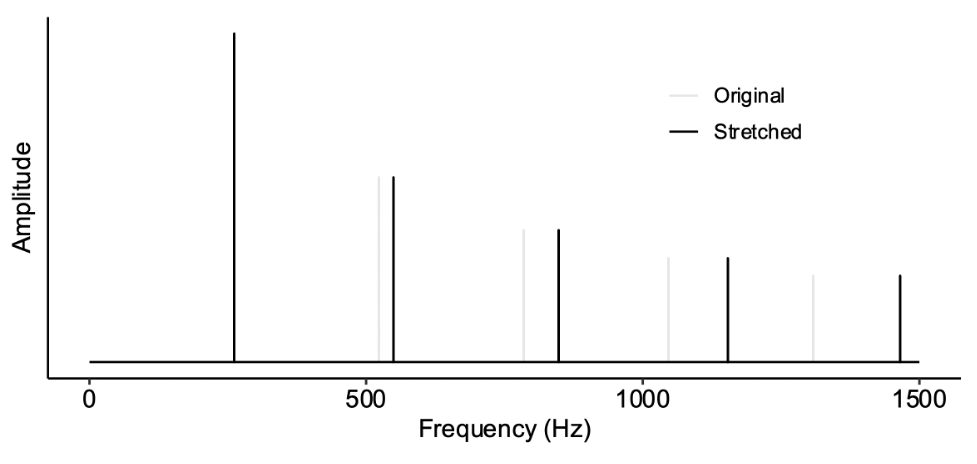

One simple yet powerful manipulation is to stretch the harmonics in a tone. The following image illustrates a harmonic spectrum that has been stretched such that the octave corresponds to a 2.1:1 frequency ratio:

Below we have a normal harmonic spectrum, where the octave corresponds to a 2.1 ratio:

It turns out that, when we stretch the tone spectra in this way, the consonance profiles also stretch. In the below figure, we see that the peaks in the pleasantness ratings (top) no longer correspond to the simple integer ratios, but rather correspond to stretched versions of these integer ratios. This phenomenon is predicted by the interference model (in red), but is not predicted by the periodicity/harmonicity model (blue). This provides strong evidence that interference between partials does contribute in some way to consonance.

Data from Marjieh, Harrison, Lee, Deligiannaki, & Jacoby. (in preparation)

Bill Sethares has produced a compelling musical illustration of this phenomenon. First, we hear a simple musical extract played with harmonic complex tones in the conventional 12-tone scale. It sounds consonant, as we might expect (listen here). Next, we play the same extract but on a stretched scale, where the octave corresponds to a 2.1 frequency ratio (listen here). The extract now sounds very dissonant, because the harmonics don’t align with the musical scale. Finally, we stretch the tone spectra to match the stretched scale (listen here). As predicted by the interference theories, the music becomes consonant again.

10.2.4 Regression modelling

These previous strategies are useful for demonstrating whether or not a particular mechanism contributes to consonance perception. However, they’re not so good for telling us how much these different mechanisms contribute to consonance perception in practice. Regression modelling is a statistical technique for doing just that: we take consonance ratings for many different chords, aggregated over many participants, and we build a statistical model that predicts these consonance ratings on the basis of computational models operationalising the main different theories of consonance. We discuss regression modelling more in Section 25.7.

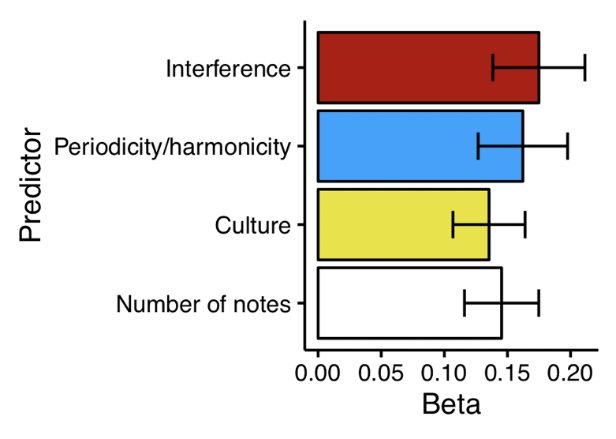

If we go through this process, the resulting models tend to point to distinct contributions of interference between partials, periodicity/harmonicity, and cultural familiarity. Here on this bar chart we have one bar for each computational model, where bar length corresponds to the extent to which the predictor contributes to the model. We see similar bar lengths for all three of the primary computational models, supporting the idea that these different mechanisms contribute jointly to consonance perception.

These results are compatible with the hypothetical causal diagram from earlier in this section. In general, the results of empirical studies are consistent with the idea that consonance derives from multiple chord features, including a potential feedback loop that amplifies certain effects through cultural learning.

References

Harrison, P. M. C., & Pearce, M. T. (2020). Simultaneous consonance in music perception and composition. Psychological Review, 127(2), 216–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000169

Hutchinson, W., & Knopoff, L. (1978). The acoustic component of western consonance. Interface, 7(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09298217808570246

McDermott, J. H., Lehr, A. J., & Oxenham, A. J. (2010). Individual differences reveal the basis of consonance. Current Biology, 20(11), 1035–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.019

McDermott, J. H., Schultz, A. F., Undurraga, E. A., & Godoy, R. A. (2016). Indifference to dissonance in native amazonians reveals cultural variation in music perception. Nature, 535(7613), 547–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18635